Disclaimer

This entry contains information known to us from a variety of sources but may not include all the information currently available. Please be in touch if you notice any inadvertent mistakes in our presentation or have additional knowledge or sources to share. Thank you.

Archive

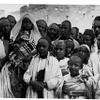

Habbani Warrior Tribal Group, Habban, Yemen

Habban lies on the western border of Ḥaḍramawt, formerly ruled by the Wāḥidī Sultanate (1).

Description

|

Background on Jews in Yemen (site description continued below): Although tradition states that Jews initially arrived in Yemen forty-two years before the destruction of the First Temple, the first archaeological evidence of Jews in Yemen comes from about 110 BCE, referring to the approval of Himyarite Kings for the constructions of synagogues. Moreover, many Jews fled from Judea to Yemen after the Bar-Kokhba revolt, and by the 550s CE Yûsuf ’As’ar Yath'ar became the first known Jewish king of the Himyarites, although the details of his life are not well defined. Throughout the centuries, Jews faced alternating waves of oppression and prosperity. Depending on the whims of political and religious leaders, Jews were prosperous merchants or craftsmen that were allowed to live comfortable lives. Yemenite Jews were known as talented silversmiths, weavers, blacksmiths, potters, and more. At other times, Jews were forced to pay heavy taxes, or to convert to Islam or be killed. One of the traumatic events of Yemenite Jewish history occurred in 1679 when the Jews of Yemen were exiled to the arid region of Mawza. Jews largely traveled to the region on foot through dangerous terrain, and the conditions of Mawza were difficult to survive. The exile lasted only a year because surrounding communities needed Jews’ services and products, but most Jews’ properties and possessions had been seized by their neighbors, so Jews returned from exile only to find they had nothing left. The pain of the Mawza expulsion hugely influenced the poetry of Shalom Shabazi, who was venerated amongst both the Jews and Muslims of Yemen. Some Yemenite Jews practiced Shami, Sephardic liturgy, but most did not assimilate to these customs and continued to follow Baladi, which adhered to Yemenite traditions and the rulings of Maimonides. Indeed, Maimonides corresponded with Yemenite scholars and praised the Jews of Yemen for their dedication to Torah and Jewish customs. In the Middle Ages, the Ottoman Empire took control of Yemen, allowing Jews easier access and communication with other Jewish communities. Ideas such as Kabbalah were popular amongst Jewish Yemenite scholars. With over 430 flights, "Operation Magic Carpet" brought 48,818 Yemeite Jews to Israel during 1949-50. Operation Magic Carpet was an initiative by the newly formed Israeli government to use passenger planes to transport the Jews of Yemen back to Israel. Before Operation Magic Carpet, most Jews first made their way to Aden, a British colony, in order to gain passage to Palestine, which was also controlled by Britain. Even before Operation Magic Carpet, the Jews of Yemen had a strong desire to make aliyah: Between 1911-49, 18,000 Jews escaped to Palestine. As of March 28, 2021, only six Jews remain in Yemen due to extreme antisemitism and violence. Notably, Levi Salem Marhabi is currently jailed in Sana’a by Houthis for helping to smuggle a Torah out of Yemen. |

Habbani Warrior Tribal Group:

Known as one of the oldest Jewish communities in South Yemen, Habbani Jews were completely isolated from other Jewish communities due to their insular and distant community. This allowed the Jews of Habban to retain ancient traditions with fewer major alterations than other diasporic communities.

There is no one concrete origin story for the Jews of Habban. Some claim that the southern Yemenite Jews are descendant of Judeans who settled in the area after the destruction of the Second Temple. Supposedly, the military groups sent by King Herod to assist the Roman troops fought in this region (2). Some scholars believe that the Habbani Jews came to Southern Yemen around 3,000 years ago during the reign of the Queen of Sheba. Others claim that the Habbani could have been Himyarite proselytes converted by Babylonian Jews during the reign of Jewish king Abu Dhu Nuwas, circa 525 C.E. (3). It is interesting to note that in Habbani genealogy is that there is no trace of Kohen or Levite ancestry, two out of the twelve tribes of Israel.

By the 16th century the Habbani Jews already resided in a Jewish Quarter (Ḥārat al-Yahūd), located on the slopes of a hill (4). Suleiman al-Hakim, a Jew, advised the Sultan in military strategies to end an ongoing siege of Habban. In return, the Suleiman received living area right next to the palace, the best residential location in the city, which became the Jewish Quarter (5). The Jewish Quarter and the Muslim Quarter were separated by the sultan’s palace (6).

Most Jews were gold or silversmiths, but Habban was known to produce incense, d̲h̲ura and barley. Habban is located on a trade route between Bāl Hāf and Mark̲h̲a and was known to trade tobacco, cotton and cloth against coffee and salt (7).

The major Jewish families of Habban were the al Adani, Doh, Hillel, Maifa'i, Ma'tuf, Shamakh, Bah'quer and D'gurkash. Nowadays all but two of the tribes still remain. The Bah’quer and D’gurkahs clans were wiped out during a severe drought in the 1700s. As the town was dying the two clans left to seek sustenance for their families. The community reached its lowest population numbers during the drought with only around 50 Habbani Jews left in the village (8). When the travelers returned they discovered that their families had died of starvation. The two clans then left the village to start a new life elsewhere (9).

Southern Yemen is known for its strict caste structure, and Jews were highly placed in the caste system (10). Furthermore, they were allowed to wear a belt and jambiyya, a decorated and curved dagger, that symbolized belonging to a higher caste (11). Habbani Jewish men had long hair but no sidelocks, and wore multi-colored fabrics with a decorated belt, just like their Muslim tribal neighbors. Women wore nets decorated with silver jewelry around their heads and were also allowed to wear wide silver belts. Before Operation Magic Carpet, they used to carry weapons and took part in inter-tribal battles of the Muslims. Furthermore, the homes of Habbani Jews were usually between two and five stories, which were taller than local regulations allowed (12).

When Zionist emissary, Shmuel Yavnieli was captured by eight Bedouins in Southern Yemen in 1912, the Habbani Jews paid his ransom and rescued him. He described his rescuers as:

"The Jews in these parts are held in high esteem by everyone in Yemen and Aden. They are said to be courageous, always with their weapons and wild long hair, and the names of their towns are mentioned by the Jews of Yemen with great admiration."(13)

Around the middle of the 20th century the Jewish quarter was made up of sixteen buildings, with two ritual baths, a cemetery outside the city, and two synagogues with adjoining schools. These synagogues observed an amalgamation of the local old rite (baladī) and the newer Sephardi rite (shāmī) from abroad (14). The synagogues also functioned as religious courts.

Due to the isolation of the Habbani Jewish community – it would take a week’s walk by foot to reach another Jewish community – most of the community was inbred and polygamy was common (15). The rise of Arab nationalism worsened the situation for Habbani Jews who were used to a relatively peaceful existence in Southern Yemen. By the middle of the 20th century the Jewish population of Habban was 375 Jews (16).

After the creation of the state of Israel, only 10% to 15% of Habbani Jews left for Aliyah. Even their Muslim neighbors did not want the Jews to leave, offering bribes so that the community would remain. Moreover, Sultan Sulṭān Nāṣir ibn 'Abd Allah ibn Muḥsin barred Habbani Jews from leaving Yemen. Jews were only allowed to leave to Aden and then fly to Israel once the sultan suddenly died and messengers from the State of Israel paid a ransom for each Jew that left (17). Most Habbani Jews did not want to leave Yemen, but the fear of being the only Jewish community left on the Arabian Peninsula eventually led to their evacuation during “Operation Magic Carpet”, in 1950 (18). Around 1,600 Habbani Jews live in Israel now (19).

Abir:

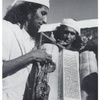

While the Habbani Jews were primarily silver and goldsmiths, many Jews also served as mercenaries and bodyguards for the sultans, imams, and sheiks due to their astonishing capabilities as warriors (20). The Habbani Jews had a special fighting style, known as Abir, that mimicked the shapes of the Hebrew alphabet. The origin of the fighting style is unknown, but is said to have been passed down through generations, starting with Abraham who learned the style from his father Abir-Qesheth (21). The fighting technique was used during the wars against the Babylonians and the Romans. After the destruction of the Temples, the art was brought to Persia and the Arabian Peninsula, where Jewish warriors formed the Bani Abir society (“son’s of Abir”) (22). Ultimately, many these warriors ended up settling in Habban (23).

Rav Yoseph Maghori Kohen shlit”a, 60-year old, Yemenite-born (Baladi) Torah scholar and scribe:

“The Habbanis were mighty heroes. I heard a lot from elders in my youth about the Habbanis, about their wars, how they would fight ‘according to names’. What does it mean ‘according to names’? –the letters: They would make the shape of the [Hebrew] letters with their hands, and by this they would be victorious.…”

The fighting style went “underground” during the emigration to Israel in the 1940’s. Only in 2001 was Abir reintroduced to the Israeli people, and allowed to be openly taught. In 2008, the Israel Sport Authority recognized Abir as an Israeli self-defense system and fighting art (24).

Sources

Background on Jews in Yemen

A. Jamme, W.F., Sabaean and Ḥasaean Inscriptions from Saudi Arabia, Instituto di Studi del Vicino Oriente: Università di Roma, Rome 1966, p. 40

Rachel Yedid & Danny Bar-Maoz (ed.), Ascending the Palm Tree – An Anthology of the Yemenite Jewish Heritage, E'ele BeTamar: Rehovot 2018, pp. 21–22

Schechtman, Joseph B. "The Repatriation of Yemenite Jewry." Jewish Social Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 1952, pp. 209-224.

Ratzaby, Yehuda, and Yosef Tobi. "Mawza'." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 13, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, p. 694. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587513436/GVRL?u=mlin_m_wellcol&sid=summon&xid=2a53428a. Accessed July 2021.

“Wrongful Detention by the Houthis of Levi Salem Musa Marhabi.” U.S. Embassy in Israel, 12 Nov. 2020, https://il.usembassy.gov/wrongful-detention-by-the-houthis-of-levi-salem-musa-marhabi/.

Yosef Tobi. ‘Mawzaʿ, Expulsion of’. Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Ed. Norman A. Stillman et al. Brill Reference Online. Web. July 2021.

Habbani Warrior Tribal Group

1. Tobi, Yosef. "Ḥabbān." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 173-174. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587508079/GVRL?u=mlin_m_wellcol&sid=summon&xid=341d5c80.

2. "Jews of Habban." Kosher Delight. Accessed July 04, 2016. http://www.kosherdelight.com/Yemen_Jews_of_Habban.shtml.

3. Ken Blady, and Steven Kaplan. Jewish Communities in Exotic Places. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 2000: 32.

4. Tobi, Yosef. "Ḥabbān." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 173-174. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587508079/GVRL?u=mlin_m_wellcol&sid=summon&xid=341d5c80.

5. Loeb, Laurence. "Habban." In Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, by Norman A. Stillman. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

6. Tobi, Yosef. "Ḥabbān." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 173-174. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587508079/GVRL?u=mlin_m_wellcol&sid=summon&xid=341d5c80

7. Schleifer, J., and Irvine, A.K. ‘Ḥabbān’. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Ed. P. Bearman et al. Brill Reference Online. Web. 11 July 2021.

8. Ingrams, D. 1949 A survey of social and economic conditions in the Aden Protectorate.

9. "Jews of Habban." Kosher Delight. Accessed July 04, 2016. http://www.kosherdelight.com/Yemen_Jews_of_Habban.shtml.

10. Blady, Jewish Communities in Exotic Places, p. 33.

11. Loeb, Laurence. "Habban." In Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, by Norman A. Stillman. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

12. Tobi, Yosef. "Ḥabbān." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 173-174. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587508079/GVRL?u=mlin_m_wellcol&sid=summon&xid=341d5c80

13. Abir - Qesheth Hebrew Warrior Arts

14. Tobi, Yosef. "Ḥabbān." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 173-174. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587508079/GVRL?u=mlin_m_wellcol&sid=summon&xid=341d5c80

15. Loeb, Laurence. "Habban." In Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, by Norman A. Stillman. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

16. Towne, "Generational Change”: 86.

17. Tobi, Yosef. "Ḥabbān." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 173-174. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587508079/GVRL?u=mlin_m_wellcol&sid=summon&xid=341d5c80

18. Lex Weingrod. Studies in Israeli Ethnicity: After the Ingathering. New York: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, 1985: 205.

19. Blady, Ken, and Steven Kaplan. Jewish Communities in Exotic Places. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 2000, p. 41.

20. "Abir - Qesheth Hebrew Warrior Arts (אביר)." Abir - Qesheth Hebrew Warrior Arts (אביר). Accessed July 04, 2016. http://www.abir.org.il/gallery2/v/movies/Abir_Qesheth_Hebrew_Warrior_Arts.html.

21. "The History of Abir." The History of Abir. Accessed July 04, 2016. http://www.abirwarriorarts.com/en/content/history-of-abir.

22. Ibid.

23 ."A Living Memory of the Bravery & Might of the Habbani Warriors Continues among Baladi Yemenite Jews." Torat Moshe RSS. July 8, 2008. Accessed July 04, 2016.

24. "A Living Memory of the Bravery & Might of the Habbani Warriors Continues among Baladi Yemenite Jews."

Further Reading on Habbani Customs:

Admin. "What Happened to the Jews of Arabia?" JEWSNEWS. 2015. Accessed July 30, 2016. http://www.jewsnews.co.il/2015/07/29/what-happened-to-the-jews-of-arabia.html.

"A Living Memory of the Bravery & Might of the Habbani Warriors Continues among Baladi Yemenite Jews."

Dux, Frank. "Abir Qesheth and Its Patriarchs: Say's Who? Part 1." Traditional Based World Wide Dojo RSS. 2012. Accessed July 30, 2016. http://www.worldwidedojo.com/traditional-based/the-lost-tribe-of-israel-roots-in-traditional-asian-martial-arts-abir-qesheth-and-its-patriarchs/.

"HOUSE OF SOLOMON." Pinterest. Accessed July 30, 2016. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/492370171737809772/.

Sienna, Noam. “Eshkol HaKofer: Lost and Found? Henna Art Among Yemenite Jews.” Eshkol HaKofer, 4 Feb. 2014, https://eshkolhakofer.blogspot.com/2014/02/lost-and-found-henna-art-among-yemenite.html.

Torat Moshe RSS. July 8, 2008. Accessed July 04, 2016. http://www.torathmoshe.com/2008/07/a-living-memory-of-the-bravery-might-of-the-habbani-warriors-continues-among-baladi-yemenite-jews/.