Disclaimer

This entry contains information known to us from a variety of sources but may not include all the information currently available. Please be in touch if you notice any inadvertent mistakes in our presentation or have additional knowledge or sources to share. Thank you.

Archive

Tomb of Nahum at al-Qosh, Iraq

There is a Kurdish-Jewish saying: "He who hasn’t witnessed the celebration of pilgrimage to Nahum’s Tomb has not seen real joy." Bearing a name that translates to "The God of Righteousness" or "The God of Power" the village of Al-Qosh, in Iraqi-Kurdistan is located at the foot of the eponymous mountains. The Assyrians of the Nineveh plain (a series of villages in present-day Northern Iraq that includes Alqosh) were among the first that accepted Christianity and the words of Jesus Christ, but this Christian village played a significant part in local Jewish history and culture and still preserves a Jewish shrine in its midst. Beneath the majestic ridge-line are the crumbling remains of the al-Qoosh shrine to the Prophet Nahum, which may be in the process of being restored.1 Now a dilapidated structure, the tomb was for centuries a major pilgrimage destination. On the holiday of Shavuot (Pentecost), commemorating the giving of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai, thousands of Kurdish Jews would gather at the top of the mountain then descend toward the shrine. Women and men would surround Nahum’s tomb singing songs celebrating the prophet.2 When the Iraqi Kurdish Jewish community emigrated en masse to Israel in 1951, guardianship of the shrine was passed to the local Christian community, who preserve the site. Throngs of Jewish pilgrims have yet to return.

Description

Location and Geography

The village of Alqosh has been documented through satellite imagery done by the British Institute for the Study of Iraq. The images show the Jebel Alqosh (Jebel meaning mountains) with springs to the north fed by what appears to be an underlying canal. It is postulated that this spring to the north of the Jebel Alqosh was the initial source for the nearby Faida canal. Alqosh is also surrounded by a relatively arid southern valley in which crops are planted, as well as a stream to its west.

Nahum the Prophet

Little is known about the prophet Nahum, with the opening verse of the Biblical book named after him only revealing that he is from “El-Kosh.”3 It is unclear which town this refers to or whether Nahum is actually buried in the shrine that bears his name in al-Qosh, Iraq. (Several other sites claim Nahum’s tomb.4) Nonetheless, for centuries thousands of Jews from across Kurdistan would make an annual pilgrimage to the site for a celebration lasting days. Nahum’s prophecy in the Bible is a rousing call made while in exile, which perhaps resonated strongly with Kurdish Jews who emigrated to Israel.

Town

While al-Qosh is a Christian village, Nahum’s tomb was owned and administered by the Jewish community (unlike the Muslim-controlled nearby tomb of Jonah in Nineveh). During the Shavuot pilgrimage, the presence of thousands of Jews wearing fine clothes and jewelry in a remote Christian village could invite theft and attack. Authorities would send police to keep the peace. Yet the local Christians did not bother Jews or damage the compound, as they also revered Nahum (many local Muslims also consider the site holy). Jewish pilgrims traveling by donkey from Mosul often required several days to reach al-Qosh, and would often spend the night in Christian villages along the way. Only in the 1920s did people start coming by car and bus.

Compound

In addition to the main hall surrounding Nahum’s tomb, the compound had tens of apartments and rooms to accommodate pilgrims. According to one source, the complex is hundreds of years old and underwent a major renovation in 1796 under the direction of Yaakov Gabbai and David Barzani. Construction funds were provided by Sasson Saleh David Yaakov, who was the head of the Baghdad Jewish community, and by Abdullah Yosef, a community leader from Basra.

Families from the Jewish community in Mosul took responsibility for maintaining the compound and hiring the guard, who lived in a nearby apartment. The last residing Jewish guard was Moshe al-Qoshi who lived there with his family. In the 20th Century, Sasson Rahamim Tzemah of Mosul spent many years and significant funds renovating the site. When the Kurdish Jewish community moved to Israel in 1951, Tzemah left the tomb in the hands of the local Christians.

Diarna Insights No. 2: the al-Qosh Shrine to Nahum

Tomb

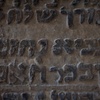

There are suggestions that parts of this tomb were also built during the late 1100s to early 1200s. With different features all from different periods of time such as Southern Turkish style medieval Artukid architecture of the thirteenth century, sixteenth century shell squinches in Islamic style and a door taken from an earlier building, the estimates of the dating rely on nearby Christian buildings.5 A visitor to the shrine during World War I described how the door was opened to visitors by a guardian with a large key on a long chain attached to his clothing. Persian carpets covered the floor. The walls of the compound contained hand-written Hebrew notes: prayers left by visitors, similar to notes tucked into Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall. In the middle of the main room, closed with an iron lock, stood a tall case covered in a green calico cloth with a gold crown on top. Today, a faded green cloth also surrounds the sarcophagus and Hebrew plaques remain on the walls, though the roof of the shrine has partially collapsed and several walls are crumbling.6

Shavuot in Alqosh

In addition to the array of monasteries and shrines that decorate the village, including the famous Rabban Hurmiz Monastery, it is also believed to be home to the site of the Prophet Nahum’s tomb. For centuries the tomb and surrounding landscape, now largely in ruins, played host to a major Shavuot pilgrimage with elaborate rituals, which last occurred in 1951. Shavuot was known locally as “Eid al-Ziyara” or “Ezyara,” Judeo-Arabic for “festival of the pilgrimage.” While individual pilgrims visited the shrine throughout the year, during the Shavuot season several thousand people–some sources say almost the entire Jewish population of Mosul and surrounding villages–would arrive en masse.7 The pilgrimage associated with the Shavuot inspired the young and old to come together in special holiday dress, to camp in the compound’s guest houses or in tents spread out in the surrounding fields; some extended their stay to the full two weeks. The highlight of the pilgrimage was a dramatic staging of the giving of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai, and a play supposed to pre-figure the battle of Gog and Magog. While there are some varying accounts of the festivities, it is said that the Shavuot would begin with an entourage carrying Torah scrolls, which would be carried to the top of a mountain known as Mont Sinai. A brief ceremonial reading of the scrolls would ensue, followed by readings from the Book of the Prophet Nahum.8

Battle

A highlight of the pilgrimage was a dramatic re-enactment of the giving of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai. The play pre-figured the battle of Armageddon, supposedly heralding the coming of the Messiah, and a boisterous prayer service circled Nahum’s tomb. (See accounts 1, 2 and 3 of the festivities.)

The theatrics began after a dawn service on the first day of Shavuot. Led by an entourage carrying Torah scrolls, a large group climbed for three hours to the top of the nearby mountain called “Mount Sinai” by locals. A brief mountain top ceremony featured a recitation of prayer commemorating the giving of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai. Then hundreds would descend the mountain in a war-like procession, accompanied by drummers and men carrying swords. At the foot of the mountain, armed men enacted a battle with loud cries, clouds of dust, and the sound of clashing weapons evoking the battle of Armageddon.

Celebration

Later, inside the tomb, an hour-long celebration featured a reading of an old scroll of the Book of Nahum. Men would surround the tomb and women listened from the outer complex. Following the reading, the men organized in alphabetical order and marched seven times around the tomb, singing sacred songs. At the seventh circling, the crowd would break into a hymn: “Rejoice in the joy of the Prophet Nahum!” At this point women joined the procession around the tomb, singing prayers in Arabic and Kurdish while dancing and clapping. Overnight, fruits would be placed atop the tomb. The next day all the pilgrims would file past the tomb, make a donation, then taste a sample of the fruits.

Reports of Judaic Life in Alkosh

Also known as Elkush, a visitor to this region reported about thirty Jewish families living there in the early 19th Century. This number dropped drastically to only one reported family in 1950.

Repair

The Iraqi government and various foreigners have at times raised the prospect of restoring the tomb, though as of early 2009 no full-scale restoration has begun. While the site has decayed substantially, it is still guarded by local Christians. Nahum, who prophesied the destruction of the nearby city of Nineveh, now sees his own tomb in partial ruin. Will it ever be rebuilt? Will hundreds of pilgrims ever return to ascend and descend the neighboring “Mount Sinai,” which also stands abandoned in Iraqi Kurdistan?

Sources

Notes

1. Huw Thomas. January 4, 2007. "Tomb of Nahum in Iraq needs urgent repairs." Point of No Return: Jewish Refugees from Arab Countries. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://jewishrefugees.blogspot.com/2007/01/tomb-of-nahum-in-iraq-needs-urgent.html.

2. Murad, Emil. The Quagmire (Tel Aviv and London: Freund, 1998), 46. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=HalmYGA2NFAC&pg=PA46&dq=Nahum+tomb&lr=#v=onepage&q=Nahum%20tomb&f=false.

3. Ainsworth, William. "Appendix." A Personal narrative of the Euphrates expedition (London: Kegan, Paul, Trench & Company; 1888), 457. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=pwke0KqOcB0C&pg=PA457&dq=Nahum+tomb&lr=#v=onepage&q=Nahum%20tomb&f=false.

4. Ibid.

5. Wolper, Ethel. “Chapter Three:Synagogues and the Hebrew Prophets: The Architecture of Convergence, Coexistence, and Conflict in Pre-Modern Iraq.” Essay. In Synagogues in the Islamic World: Architecture, Design, and Identity, edited by Mohammad Gharipour, 31–46. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

6. "Iraq to renovate biblical prophet's tomb." WND, July 19, 2007. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://www.wnd.com/2007/07/42630/.

7. Erich Brauer and Raphael Patai. The Jews of Kurdistan, 298. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=Y6S7qTDomCgC&pg=PP1&dq=The+Jews+of+Kurdistan+patai#v=onepage&q=The%20Jews%20of%20Kurdistan%20patai&f=false.

8. Mendelssohn, Sidney. "Kurdistan." The Jews of Asia (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., 1920), 194-195. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=h6WBAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA194&dq=Nahum+tomb&lr=#v=onepage&q=Nahum%20tomb&f=false.

Works Cited

Ainsworth, William. "Appendix." A Personal narrative of the Euphrates expedition (London: Kegan, Paul, Trench & Company; 1888), 457. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=pwke0KqOcB0C&pg=PA457&dq=Nahum+tomb&lr=#v=onepage&q=Nahum%20tomb&f=false.

"Jewish Communities." Beit Hatfutsot Jewish Communities Database. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://www.bh.org.il/database-about.aspx?communities.

Erich Brauer and Raphael Patai. The Jews of Kurdistan. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=Y6S7qTDomCgC&pg=PP1&dq=The+Jews+of+Kurdistan+patai#v=onepage&q=The%20Jews%20of%20Kurdistan%20patai&f=false.

Huw Thomas. January 4, 2007. "Tomb of Nahum in Iraq needs urgent repairs." Point of No Return: Jewish Refugees from Arab Countries. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://jewishrefugees.blogspot.com/2007/01/tomb-of-nahum-in-iraq-needs-urgent.html.

"Iraq to renovate biblical prophet's tomb." WND, July 19, 2007. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://www.wnd.com/2007/07/42630/.

Laniado, Ezra. Yehude Motsul mi-galut Shomron ʻad mivtsaʻ ʻEzra u-Neḥemyah, (Tirat-Karmel: Makhon le-ḥeḳer Yahadut Motsul, 1981).

Layard, Austen Henry. Nineveh and its remains (New York: Routledge & K. Paul, 1970).

Mendelssohn, Sidney. "Kurdistan." The Jews of Asia (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., 1920), 194-195. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=h6WBAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA194&dq=Nahum+tomb&lr=#v=onepage&q=Nahum%20tomb&f=false.

Murad, Emil. The Quagmire (Tel Aviv and London: Freund, 1998), 46. Accessed January 6, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=HalmYGA2NFAC&pg=PA46&dq=Nahum+tomb&lr=#v=onepage&q=Nahum%20tomb&f=false.

Wolper, Ethel. “Chapter Three:Synagogues and the Hebrew Prophets: The Architecture of Convergence, Coexistence, and Conflict in Pre-Modern Iraq.” Essay. In Synagogues in the Islamic World: Architecture, Design, and Identity, edited by Mohammad Gharipour, 31–46. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Image Gallery

For more images of the site, visit:

https://www.mesopotamiaheritage.org/en/monuments/la-tombe-du-prophete-nahoum/

![Town of al-Qosh, View From “Mt. Sinai” [1] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/e3VbM9u2TziPTJzyrMeg/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Town of al-Qosh, View From “Mt. Sinai” [2] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/cCZxZaZNRxiGSRoZr8bi/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Pillar Inscription [3] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/htVnFAezRPuPVEV909iw/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Pillar Inscription [2] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/mQyt37myS5CqBvazabWT/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior [2] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/KWOzwBBbREe7M5spDCz2/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Pillar Inscription [1] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/FvQGB13STguFeK0tATAR/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Altar, Memorial Candle [2] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/Vly7jCH3S3a4qfNTouvM/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Altar, Memorial Candle [1] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/sNqWgARDR5SUaQ6WFH57/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Pillar Inscription [5] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/fLxJydd7TjOnfqVwYX9a/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Pillar Inscription [4] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/EvUBDePRzokzT5SxcKFw/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior [1] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/bfSf83YVQi2FngqZgzjr/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Sarcophagus [2] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/PSYWYRLWSSmIWueZEW4p/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Sarcophagus [1] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/Xy7ArkB7T4CflysoSeNj/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Interior, Courtyard Entrance [3] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/cJRDiMi0QGOYfSsAcqNf/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Exterior, Courtyard Entrance [2] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/MdyZHQHR6S237uSPxRwS/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Nahum, Exterior, Courtyard Entrance [1] (al-Qosh, Iraq, 2012)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/2DV0yGq4Si2U3sxFhSfT/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)