Disclaimer

This entry contains information known to us from a variety of sources but may not include all the information currently available. Please be in touch if you notice any inadvertent mistakes in our presentation or have additional knowledge or sources to share. Thank you.

Archive

Tomb of Esther and Mordechai at Hamadan, Iran

Aside from inspiring Madonna’s adopted Kabbalah name, Esther is one of the few women to have part of the Bible named after her. She was, according to the Book of Esther, a beautiful, young Persian woman who caught the eye of King Aḥashverosh. She became Queen, and with the assistance of her uncle Mordechai, saved Persian Jews from annihilation. Every year, Jews around the world celebrate this miraculous salvation during the holiday of Purim by reciting the Book of Esther, dressing in costumes and eating treats. For centuries, Iranian Jews have also marked the holiday by making a pilgrimage to a shrine in the city of Hamadan where Esther and Mordechai are traditionally held to be buried.1 The origins and contents of this shrine are shrouded in legend and mystery.

Description

History

According to legend, the original shrine was destroyed by Mongol invaders in the 14th Century.2 Historian Ernst Herzfeld dates the current structure to 1602. The shrine’s look reflects a common Persian style of that general era (known as emamzadeh) for shrines of Muslim religious leaders. 19th century visitors to the shrine describe a marble plaque on the interior dome walls stating that the structure was dedicated in the year 714 (Jewish calendar year 4474) by Elias and Samuel, sons of Ismail Kachan.3

Outstanding illustrations, photos, and descriptions of the tomb come from Christians visiting Hamadan in the 1800s and early 1900s (examples include: 1822, 1836, 1855, 1859, 1885, and 1903). All depict a solitary building set on a hill. One observer notes that most of the exterior blue tiles have fallen off.4 Another describes a stork’s nest sitting atop the domed shrine and notes that the Hamadan chief rabbi holds the key.5 Another observes that the shrine seems built for durability rather than beauty and that the area around the tomb serves as a wood market for local Muslims.6 A Columbia University professor visiting in the early 1900s says the tomb is situated in an old Jewish cemetery south of the main city.7

Renovation

Today the shrine is located smack in the center of modern Hamadan, a city anchored around the star-shaped Imam Khomeini square with six avenues spreading out along the angles of the star. Esther’s Tomb is located along the boulevard heading west toward Mount Alvand. Until 1970, the shrine was hidden away in a crowded part of Hamadan, surrounded by houses, and only accessible via a narrow dirt alley.

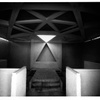

In 1971, in honor of a national celebration of 2,500 years of Iranian monarchy, the Iranian Jewish Society commissioned architect Elias Yassi Gabbay to renovate the complex. Houses around the tomb were purchased and demolished. The shrine became visible and accessible from the main street, via a bridge built over a new courtyard and partially buried modern synagogue chapel. Although contemporary in style and design, Gabbay’s addition uses the same brick and granite as that of the original tomb.8

The Restorer of Esther and Mordechai's Tomb

Elias Gabbay—today a top architect in Beverly Hills, California—reminisces about his work in the 1970s renovating and restoring the tomb. Gabbay transformed the site, adding a subterranean synagogue and creating an open entrance plaza to the shrine. Gabbay notes that the synagogue's roof—built in the shape of a Jewish star—is visible in Google Earth. He also explains how the restoration was an interfaith project

Architect Yassi Gabbay on designing the expansion of the Tomb of Esther, Hamedan, Iran

Features

The renovation did not significantly alter the grave stones cluttering the plaza outside the old shrine or the shrine itself. One of the old building’s remarkable features is its front door—a massive piece of granite with a hidden lock. Less than four feet high, the stunted door frame forces visitors to bow as they enter in deference to the site’s holy occupants.9

An outer chamber holds tombs of famous rabbis and provides access via an archway to an interior chamber that features Hebrew writing along the walls.10 The chamber also holds two carved sarcophagi, supposedly marking the burial spot below of Esther and Mordechai, as well as a cabinet with a 300-year-old torah scroll. The original sarcophaguses were destroyed in a fire, as pilgrims once lit candles directly on top of the wooden cases. The current modern coffers are imitations of the originals.

Diarna Insights No. 1: The Hamadan Shrine to Esther and Mordechai

Visitors over a century ago describe these rooms as covered in pilgrims’ graffiti in various languages as well as darkened by candle smoke.11 The two ark-shaped sarcophagi, made of ebony, were inscribed with carved Hebrew biblical passages from the Book of Esther and Psalms, as well as the genealogy connecting Mordechai back to Jacob, also known as Israel.12 An ostrich egg apparently hung from the center of the dome interior, and faded religious parchments were stored here as a sort of genizah, or a temporary storage area for old Hebrew religious texts.13

A prayer area was designed to enable worshippers to face the tombs and Jerusalem at the same time. Christian pilgrims describe seeing notes in Hebrew script attached to the tombs, similar to how Jewish worshippers often tuck prayer notes into the stones of Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall. For Iranian Jews, who could only reach Jerusalem with great difficulty, these sarcophagi served as a stand-in place to pray and weep.

Authenticity: Historians question whether Esther and Mordechai ever actually existed, and if they did, whether the Hamadan shrine actually holds their bones. For Iranian Jews and Muslims, however, the tomb has for centuries been venerated as a holy site. While the Bible describes Esther and Mordechai living in the city of Shushan (today’s Shush or Susa), the city of Hamadan (known then as Ecbatana) hosted the royal summer residence, on the slopes of Mount Alvand. Tradition has it that Esther and Mordechai, after spending their final years at the royal summer resort, were buried next to one another, and that the shrine today known as Esther’s Tomb sits over their graves.

The question of whether the shrine actually marks the grave of Esther and her uncle remains unanswered. But one 19th Century Christian pilgrim offered her own insight on the significance of the tomb and the 2,700-year-old Persian Jewish community that guards it:

“Beside the tomb of Esther the lowly race she saved have kept loving watch through all the weary ages. More wonderful than any ancient monument are these Jews themselves, lineal descendants, in blood and faith, of the tribes of Israel, and the only vestige of the truly olden time which entirely defies decay and dissolution.”

Sources

Notes

1. Church Missionary Society. The Round World and They that Dwell Therein (London: Church Missionary Society, 1903), 148-149. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=ZesYAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA148&dq=tomb+of+esther#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

2. W.A. Scott. Esther; The Hebrew-Persian Queen (San Francisco: H.H. Bancroft, 1859), 337. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=hm3rnztP_YkC&pg=PA337&lpg=PA337&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=YGe2T6VgFK&sig=PYnPUHr6x2YSW7a0hDZpx8lLywg&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=10&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

3. Ern. Frid. Car Rosenmüller and Nathaniel Morren. The Biblical Geography of Central Asia, Vol. XI (Edinburgh: Thomas Clark, 1836), 307. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=0l8ZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA307&dq=tomb+of+esther#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

4. Isabella Lucy Bird. Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1891), 153. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=KL0MAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA153&lpg=PA153&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=7DtkxUU2vq&sig=dzOn_JqTOusGTKhQPpWl1-Wd6aY&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

5. John McClintock. Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Vol. 6 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1890), 592. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=1uVOrP2tgG0C&pg=PA592&lpg=PA592&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=AIdLYdbTFh&sig=feZ-wojC9urxgx5n9xweUt2aXeI&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=5&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

6. Oriens. “The Tomb of Esther.” Our Monthly, July to December, 1872, 381. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=dNEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA381&lpg=PA381&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=_4l5pYxBS9&sig=2ZM41MderJL16-foTAxYaw7TxNU&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

7. Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson. Persia Past and Present (London: Macmillan, 1906), 168. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=7pdCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA168&lpg=PA168&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=b2_Rnnifzn&sig=3-XZBz4VD61aTkTw1r8_98TGTWQ&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

8. Gabbay Architects. “Esther’s Tomb.” Accessed January 20, 2014, http://www.gabbayarchitects.com/international.php?project_id=39&image_id=106.

9. Robert Ker Porter. “Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, Ancient Babylonia &c. &c. During the Years 1817, 1818, 1819, and 1820” Monthly Magazine, July 31, 1822, 584. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=CVMoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA584&dq=tomb+of+esther&lr=#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

10. John David Rees. Notes of a Journey from Kasveen to Hamadan Across the Karagan Country (Madras: E. Keys, 1885), 29. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=LYZCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA29&dq=tomb+of+esther&lr=#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

11. Jackson, Persia Past and Present, 168.

12. John Kitto. The Pictorial Bible: Vol. II, Judges-Job (London: W. and R. Chambers, 1855), 608. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=lTkXAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA608&lpg=PA608&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=akJuqIABuu&sig=skbmq4nh67bPZ286zeBZxsK4vek&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

13. Oriens, “The Tomb of Esther”, 381.

Works Cited

Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson. Persia Past and Present (London: Macmillan, 1906), 168. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=7pdCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA168&lpg=PA168&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=b2_Rnnifzn&sig=3-XZBz4VD61aTkTw1r8_98TGTWQ&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

Church Missionary Society. The Round World and They that Dwell Therein (London: Church Missionary Society, 1903), 148-149. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=ZesYAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA148&dq=tomb+of+esther#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

Ern. Frid. Car Rosenmüller and Nathaniel Morren. The Biblical Geography of Central Asia, Vol. XI (Edinburgh: Thomas Clark, 1836), 307. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=0l8ZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA307&dq=tomb+of+esther#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

Ernst Herzfeld Papers. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://www.asia.si.edu/archives/finding_aids/herzfeld.html.

Gabbay Architects. “Esther’s Tomb.” Accessed January 20, 2014, http://www.gabbayarchitects.com/international.php?project_id=39&image_id=106.

Isabella Lucy Bird. Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1891), 153. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=KL0MAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA153&lpg=PA153&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=7DtkxUU2vq&sig=dzOn_JqTOusGTKhQPpWl1-Wd6aY&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

John David Rees. Notes of a Journey from Kasveen to Hamadan Across the Karagan Country (Madras: E. Keys, 1885), 29. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=LYZCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA29&dq=tomb+of+esther&lr=#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

John Kitto. The Pictorial Bible: Vol. II, Judges-Job (London: W. and R. Chambers, 1855), 608. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=lTkXAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA608&lpg=PA608&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=akJuqIABuu&sig=skbmq4nh67bPZ286zeBZxsK4vek&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

John McClintock. Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Vol. 6 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1890), 592. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=1uVOrP2tgG0C&pg=PA592&lpg=PA592&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=AIdLYdbTFh&sig=feZ-wojC9urxgx5n9xweUt2aXeI&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=5&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

Oriens. “The Tomb of Esther.” Our Monthly, July to December, 1872, 381. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=dNEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA381&lpg=PA381&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=_4l5pYxBS9&sig=2ZM41MderJL16-foTAxYaw7TxNU&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

Robert Ker Porter. “Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, Ancient Babylonia &c. &c. During the Years 1817, 1818, 1819, and 1820” Monthly Magazine, July 31, 1822, 584. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=CVMoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA584&dq=tomb+of+esther&lr=#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

W.A. Scott. Esther; The Hebrew-Persian Queen (San Francisco: H.H. Bancroft, 1859), 337. Accessed January 20, 2014, http://books.google.com/books?id=hm3rnztP_YkC&pg=PA337&lpg=PA337&dq=tomb+of+esther&source=web&ots=YGe2T6VgFK&sig=PYnPUHr6x2YSW7a0hDZpx8lLywg&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=10&ct=result#v=onepage&q=tomb%20of%20esther&f=false.

Image Gallery

For more images of the site, visit:

https://www.timesofisrael.com/tomb-of-mordechai-and-esther-in-iran-reportedly-set-ablaze/

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [15] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/4N5C0hRsTViz5twrne6O/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [14] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/lWqL42UuSRaEpAr24QnM/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [13] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/I17DZI37SuuYJmHEbSdJ/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [12] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/cRwYrEiS96SqbZ3gBMF5/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [11] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/9VIedAYSdGu9ruNuJnwJ/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [10] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/8OVzL3mjRV2YUqr8G5ms/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [9] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/RVtAkpOFSw6WmSnXTzrQ/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [8] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/OkGUiXteTSm2rU6AkCn2/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Wall Inscription [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/TQXWV9SNQmSNT8SexIfD/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Wall Inscription [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/naS73ZNiSfK5vs54q3Ka/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [7] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/netLl3ZUSqeV56PALNVY/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [6] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/hHEUDCRRQE25uC1hcWSQ/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [5] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/RwRPOqx1QXiSzJcZypAH/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [4] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/vP3HLkv1SUeX1ttqswm0/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [3] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/ujV1l842RRWqbz1G68hz/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Sarcophagus [3] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/9MKftB8mTk6jrOvZCByK/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Sarcophagus [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/B5NqB1ljT8SxYrtw7iit/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/VqbdM6PeRRmFBBscAtND/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/GZPnAj2rT5iILugkR4Y7/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Sarcophagus [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/jDq1J0AwRRGDj4Mc2T42/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Entrance [4] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/T3Au98gTVaComL9OBtQS/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Entrance [3] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/bTwAAOskQ167Zf1svbr3/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Entrance [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/DOlnlb27SNCaNk0NafRj/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Interior, Entrance [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/hqODKVCTdeLoBJwe4QwJ/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior, Entrance [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/2jOdzzPQDSg1dmDyermd/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior, Entrance [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/2XdSViOgREWvDMJUHIuW/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [13] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/Xg9PXG1cSU6uCu9wjQfX/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [12] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/WwpXivvTRrSzK11MS9Gn/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [11] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/FQRurxo5REGwWQQs3EtX/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [10] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/FPL03JaSSRQ9IWO6njQw/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior, Illustration [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 19th Century)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/1Y7lm2IRQZOL57ENIYCi/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior, Illustration [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 19th Century)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/rDoNyGdTnurrIH2Lf4eQ/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [9] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/bbLXwxK1TNaubbWyjb3L/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior, Digital Reconstruction [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/JhetKAJjTMCRFxrK3RcC/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [8] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/PllAp4vlSsK9ov5vS1Hv/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [7] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/duix5rTPTi6WB3OXCHea/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [6] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/JkJYlRtGRmChFniyghTz/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [5] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/l2CSLYAeQ7qpK50CSCur/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [4] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/mwwPD1ClTMamzrjlzf15/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [3] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/IMsdZFNORE6ybK828d1i/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [2] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/2dueZByEQ0mqkAyezGJR/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior, Digital Reconstruction [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/oZMw0xCUQP6UO3euUgMh/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)

![Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Exterior [1] (Hamadan, Iran, 2011)](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/kcoPpRErR36HXY0oLeJR/convert?w=100&h=100&fit=crop)